>100 subscribers

The belief that vision happen with our eyes is only partially true. The brain captures light and assembles that light into what we experience as sight. This is how the visual system operates. Photoreceptors in the retina convert light into electrical signals.

What you "see" is already a reconstruction that's shaped by attention, memory, and the brain's predictive models

The raw data our eyes collect is incomplete. Our brain fills the gaps, suppresses irrelevant detail, and prioritizes patterns it recognizes.

Light Is Just Information

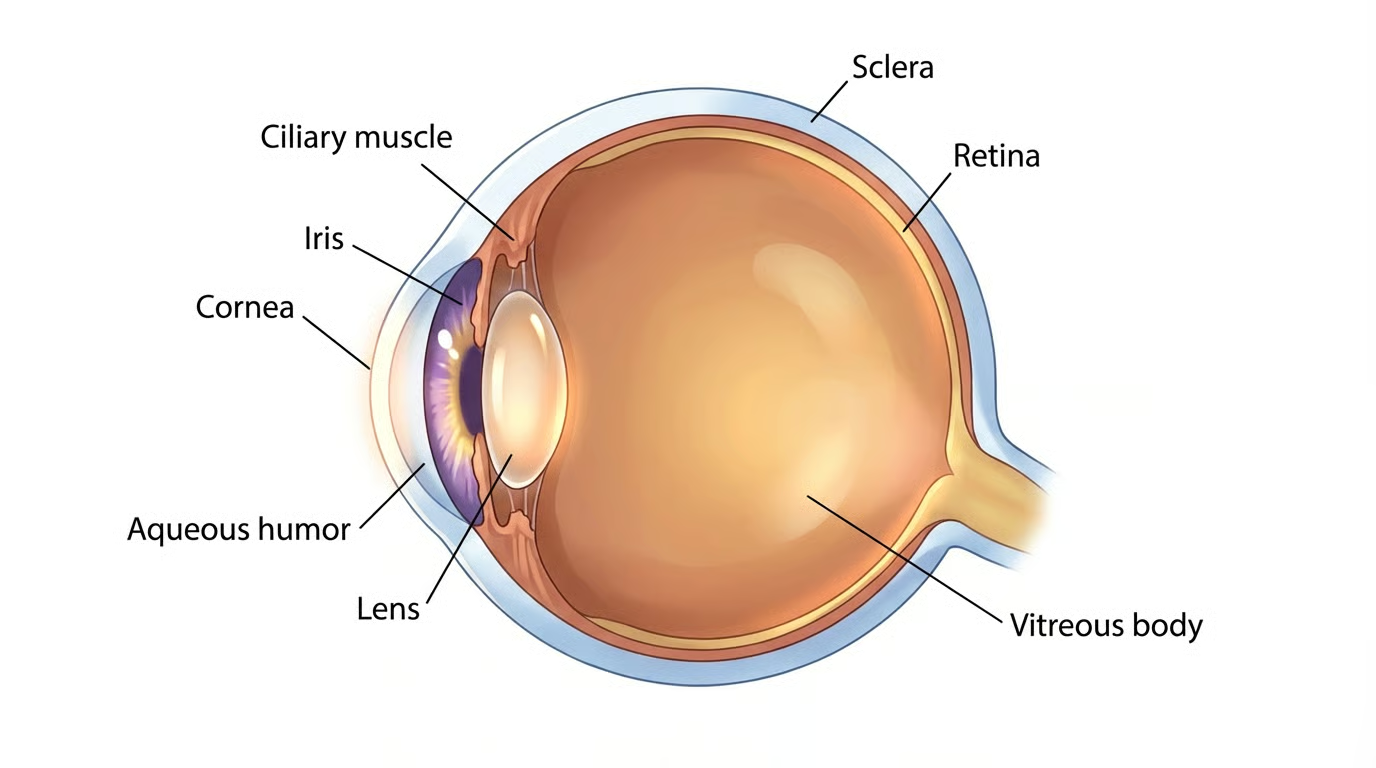

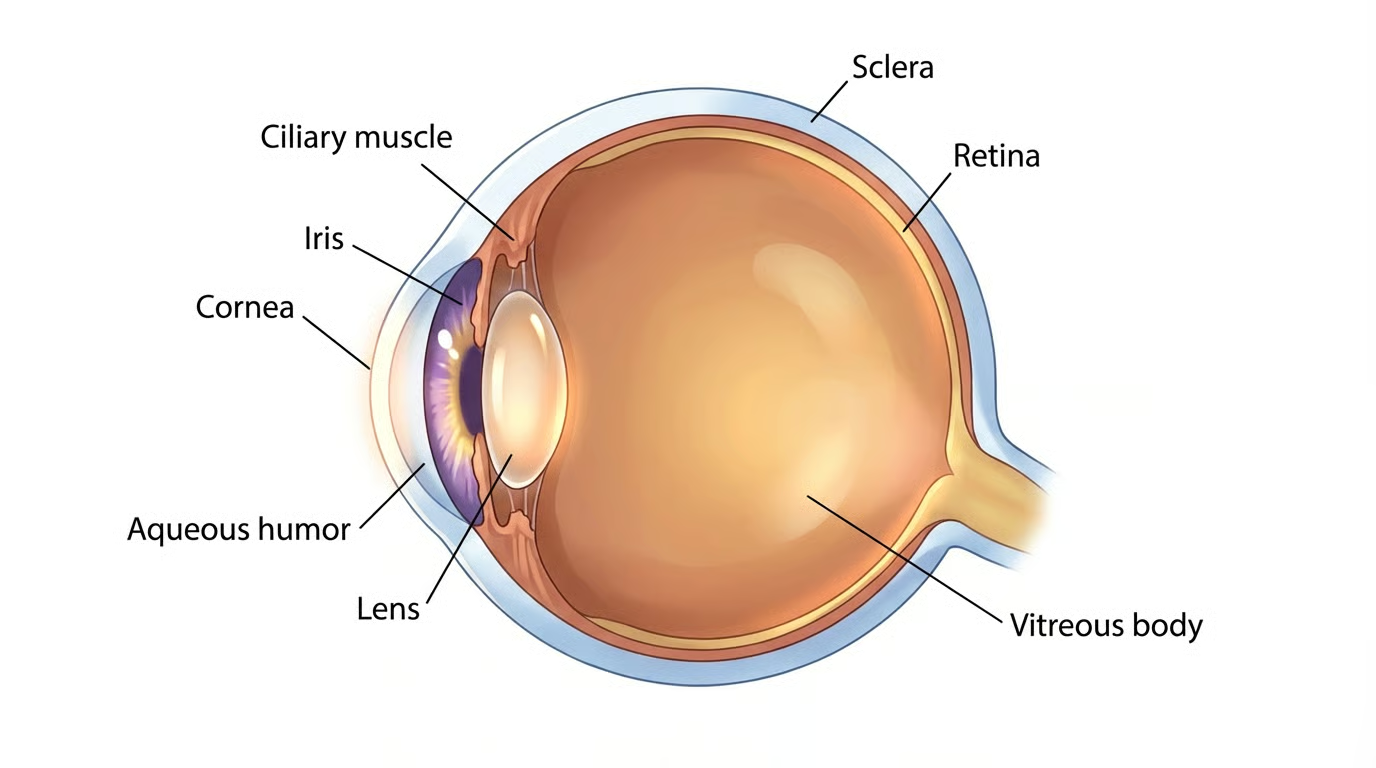

Vision begins when light from the sun reflects off objects, and enters the eye through the cornea and pupil. The lens focuses this light onto the retina, a thin sheet of neural tissue lining the back of the eye.

Importantly, the image projected onto the retina is upside down and reversed left to right.

Your brain can't handle it right now so we'll deal with it later.

What you should know is that the light has to be converted into neural signals.

Rods and Cones: Two Ways of Seeing

The retina contains two primary types of photoreceptors:

Rods

Extremely sensitive to light

Enable night vision and peripheral vision

Do not detect color

Dominate the retina outside the fovea

Rods allow you to see in dim environments but sacrifice detail.

Now lets get into the cones….

Cones

Less light-sensitive

Enable color vision and high spatial resolution

Concentrated in the fovea (central vision)

Come in three types (short, medium, long wavelength sensitive)

Cones allow you to read, recognize faces, and see fine detail — but they require bright light.

How Rods and Cones Switch Between Dark and Light

Here’s where vision becomes counterintuitive.

Unlike most neurons, photoreceptors are more active in the dark than in the light.

In Darkness

Photoreceptors continuously release glutamate

Sodium channels remain open

The cell stays relatively depolarized

This high baseline activity signals “no light detected.”

In Light

Photons activate photopigments (rhodopsin in rods, opsins in cones)

A signaling cascade closes sodium channels

The cell hyperpolarizes

Glutamate release decreases

In other words: light reduces neural firing.

Downstream retinal neurons are tuned to detect these changes, allowing the system to encode contrast, edges, and motion rather than absolute brightness.

This mechanism allows the visual system to operate across an enormous range of lighting conditions… from starlight to sunlight.

The Retina Is Already Doing Computation

Before signals ever leave the eye, the retina performs sophisticated processing through layers of bipolar cells, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells.

These circuits:

Enhance contrast

Suppress redundancy

Detect edges and motion

Separate visual features into parallel channels

By the time information reaches the brain, it has already been heavily transformed.

The retina is complex neural network.

From Eye to Brain

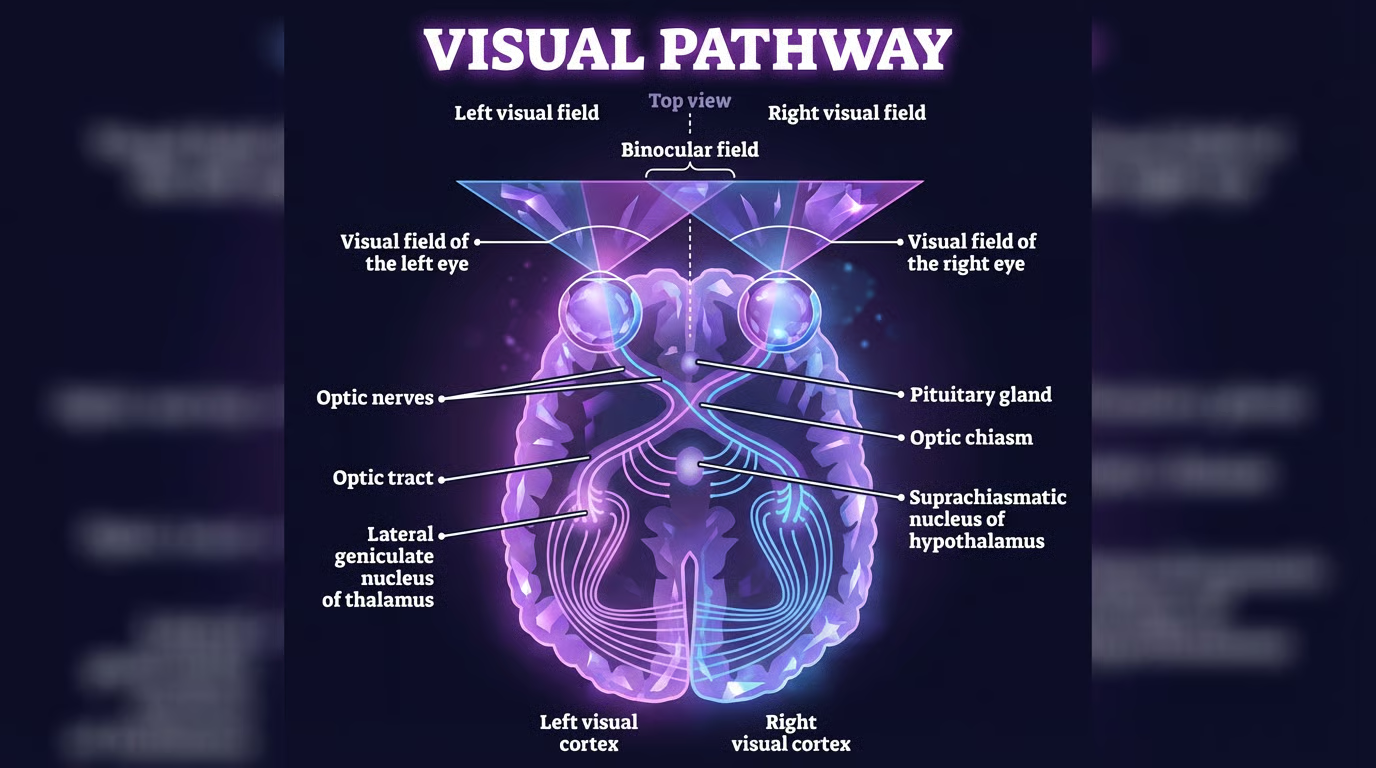

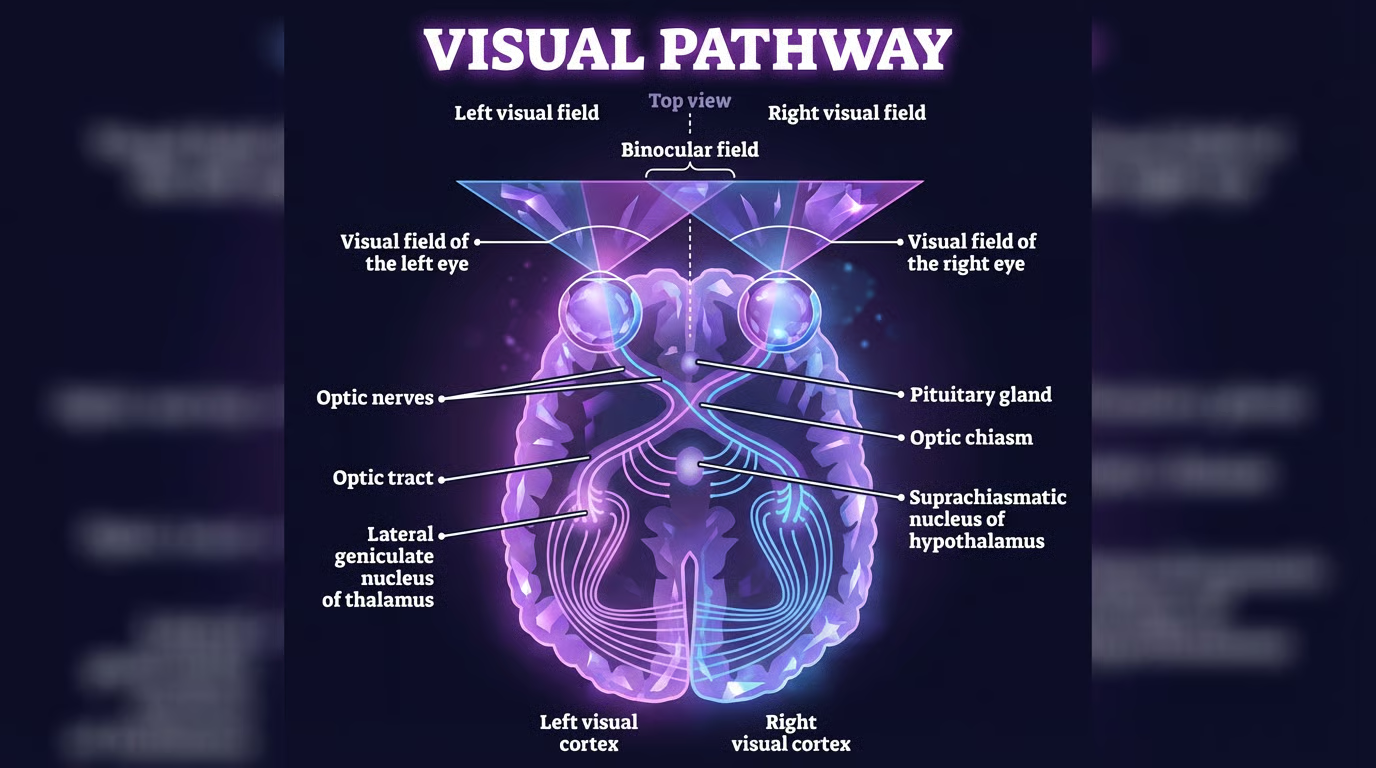

Retinal ganglion cells send visual information through the optic nerve. At the optic chiasm, fibers partially cross so that each hemisphere processes the opposite visual field.

Most signals pass through the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus, which:

Regulates signal strength

Integrates attention and arousal

Synchronizes visual input with cortical activity

What you pay attention to influences what gets through.

Seeing the World Upside Down (and Fixing It)

Because of the optics of the eye, the image on your retina is inverted. Yet you don’t experience the world as upside down. This is not because the brain “flips” the image like a photograph. Instead, the brain learns spatial relationships through sensorimotor experience.

From infancy, visual input is continuously paired with:

Movement

Touch

Balance

Proprioception

Over time, the brain builds stable mappings between retinal signals and the external world. Orientation becomes implicit, not calculated.

This is why people wearing inversion goggles (that flip the visual field) can eventually adapt and perceive the world as upright again. Vision is learned how cool is that?

The Visual Cortex Builds Perception

Visual information reaches the primary visual cortex (V1) in the occipital lobe, where neurons respond to:

Orientation

Motion

Spatial frequency

Contrast

From there, processing diverges into two major pathways:

Ventral stream (“what”): object and face recognition

Dorsal stream (“where/how”): motion, depth, spatial interaction

Vision emerges from coordinated activity across populations of neurons.

Vision Is a Prediction

Your brain constantly predicts what it expects to see and updates those predictions based on sensory input.

This explains:

Optical illusions

Context-dependent perception

Why attention changes what you notice

Why fatigue degrades vision

You don’t passively receive the world.

You infer it.

Actionable Takeaways: How to Care for Your Visual System

Vision health is brain health.

1. Respect Light Transitions. Allow time for rods and cones to adapt when moving between bright and dark environments. Sudden lighting changes strain retinal and cortical circuits.

2. Reduce Prolonged Near Focus. Sustained close-up work biases cone-heavy foveal processing. Use the 20–20–20 rule to reduce visual fatigue.

3. Protect Circadian Vision. Retinal signals regulate circadian rhythms.

Get morning daylight

Limit bright screens at night

This supports both sleep and visual clarity.

4. Support Retinal Metabolism. The retina is one of the most energy-demanding tissues in the body.

Maintain metabolic health

Prioritize omega-3 fatty acids

Reduce chronic inflammation

5. Blink Intentionally. Screen use suppresses blinking, degrading visual input quality and increasing cortical effort.

Not all vision problems come from the same place. Some are optical, some are ocular, and some are neurological.

When You Need Glasses. Glasses and contacts correct refractive errors, meaning light is not focused cleanly onto the retina.

Nearsightedness (myopia): distance blur

Farsightedness (hyperopia): near strain or blur

Astigmatism: distorted vision

Presbyopia: age-related difficulty focusing up close

In these cases, the brain is healthy but the image it receives is blurry. Glasses sharpen the signal.

When the Eye Is the Problem. Some conditions damage the eye or retina itself, and glasses cannot fix them.

Cataracts: cloudy lens, reduced contrast

Macular degeneration: loss of central detail

Glaucoma: gradual peripheral vision loss

Retinal disease: disrupted photoreceptor function

When the Brain Is the Problem. Vision can fail even with healthy eyes.

Stroke or brain injury

Visual processing disorders

Difficulty recognizing objects or motion

Here, the eyes detect light, but the brain cannot interpret it correctly.

When to Get Checked. Seek evaluation for sudden vision changes, loss of peripheral vision, flashes of light, or vision changes with headaches or neurological symptoms.

I hope you enjoyed learning about the visual system!

With love,

Dr. Azura Plantiff

Selected References

Masland R. H. (2012). The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron, 76(2), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.002

Hubel, D. H., & Wiesel, T. N. (1968). Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. The Journal of physiology, 195(1), 215–243. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008455

By Eric R. Kandel, John D. Koester, Sarah H. Mack and Steven A. Siegelbaum (2021). Principles of Neural Science, Sixth Edition, 6th Edition. McGraw-Hill.

Livingstone, M., & Hubel, D. (1988). Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science (New York, N.Y.), 240(4853), 740–749. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3283936

Nassi, J. J., & Callaway, E. M. (2009). Parallel processing strategies of the primate visual system. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 10(5), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2619

Friston K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

The belief that vision happen with our eyes is only partially true. The brain captures light and assembles that light into what we experience as sight. This is how the visual system operates. Photoreceptors in the retina convert light into electrical signals.

What you "see" is already a reconstruction that's shaped by attention, memory, and the brain's predictive models

The raw data our eyes collect is incomplete. Our brain fills the gaps, suppresses irrelevant detail, and prioritizes patterns it recognizes.

Light Is Just Information

Vision begins when light from the sun reflects off objects, and enters the eye through the cornea and pupil. The lens focuses this light onto the retina, a thin sheet of neural tissue lining the back of the eye.

Importantly, the image projected onto the retina is upside down and reversed left to right.

Your brain can't handle it right now so we'll deal with it later.

What you should know is that the light has to be converted into neural signals.

Rods and Cones: Two Ways of Seeing

The retina contains two primary types of photoreceptors:

Rods

Extremely sensitive to light

Enable night vision and peripheral vision

Do not detect color

Dominate the retina outside the fovea

Rods allow you to see in dim environments but sacrifice detail.

Now lets get into the cones….

Cones

Less light-sensitive

Enable color vision and high spatial resolution

Concentrated in the fovea (central vision)

Come in three types (short, medium, long wavelength sensitive)

Cones allow you to read, recognize faces, and see fine detail — but they require bright light.

How Rods and Cones Switch Between Dark and Light

Here’s where vision becomes counterintuitive.

Unlike most neurons, photoreceptors are more active in the dark than in the light.

In Darkness

Photoreceptors continuously release glutamate

Sodium channels remain open

The cell stays relatively depolarized

This high baseline activity signals “no light detected.”

In Light

Photons activate photopigments (rhodopsin in rods, opsins in cones)

A signaling cascade closes sodium channels

The cell hyperpolarizes

Glutamate release decreases

In other words: light reduces neural firing.

Downstream retinal neurons are tuned to detect these changes, allowing the system to encode contrast, edges, and motion rather than absolute brightness.

This mechanism allows the visual system to operate across an enormous range of lighting conditions… from starlight to sunlight.

The Retina Is Already Doing Computation

Before signals ever leave the eye, the retina performs sophisticated processing through layers of bipolar cells, horizontal cells, and amacrine cells.

These circuits:

Enhance contrast

Suppress redundancy

Detect edges and motion

Separate visual features into parallel channels

By the time information reaches the brain, it has already been heavily transformed.

The retina is complex neural network.

From Eye to Brain

Retinal ganglion cells send visual information through the optic nerve. At the optic chiasm, fibers partially cross so that each hemisphere processes the opposite visual field.

Most signals pass through the lateral geniculate nucleus (LGN) of the thalamus, which:

Regulates signal strength

Integrates attention and arousal

Synchronizes visual input with cortical activity

What you pay attention to influences what gets through.

Seeing the World Upside Down (and Fixing It)

Because of the optics of the eye, the image on your retina is inverted. Yet you don’t experience the world as upside down. This is not because the brain “flips” the image like a photograph. Instead, the brain learns spatial relationships through sensorimotor experience.

From infancy, visual input is continuously paired with:

Movement

Touch

Balance

Proprioception

Over time, the brain builds stable mappings between retinal signals and the external world. Orientation becomes implicit, not calculated.

This is why people wearing inversion goggles (that flip the visual field) can eventually adapt and perceive the world as upright again. Vision is learned how cool is that?

The Visual Cortex Builds Perception

Visual information reaches the primary visual cortex (V1) in the occipital lobe, where neurons respond to:

Orientation

Motion

Spatial frequency

Contrast

From there, processing diverges into two major pathways:

Ventral stream (“what”): object and face recognition

Dorsal stream (“where/how”): motion, depth, spatial interaction

Vision emerges from coordinated activity across populations of neurons.

Vision Is a Prediction

Your brain constantly predicts what it expects to see and updates those predictions based on sensory input.

This explains:

Optical illusions

Context-dependent perception

Why attention changes what you notice

Why fatigue degrades vision

You don’t passively receive the world.

You infer it.

Actionable Takeaways: How to Care for Your Visual System

Vision health is brain health.

1. Respect Light Transitions. Allow time for rods and cones to adapt when moving between bright and dark environments. Sudden lighting changes strain retinal and cortical circuits.

2. Reduce Prolonged Near Focus. Sustained close-up work biases cone-heavy foveal processing. Use the 20–20–20 rule to reduce visual fatigue.

3. Protect Circadian Vision. Retinal signals regulate circadian rhythms.

Get morning daylight

Limit bright screens at night

This supports both sleep and visual clarity.

4. Support Retinal Metabolism. The retina is one of the most energy-demanding tissues in the body.

Maintain metabolic health

Prioritize omega-3 fatty acids

Reduce chronic inflammation

5. Blink Intentionally. Screen use suppresses blinking, degrading visual input quality and increasing cortical effort.

Not all vision problems come from the same place. Some are optical, some are ocular, and some are neurological.

When You Need Glasses. Glasses and contacts correct refractive errors, meaning light is not focused cleanly onto the retina.

Nearsightedness (myopia): distance blur

Farsightedness (hyperopia): near strain or blur

Astigmatism: distorted vision

Presbyopia: age-related difficulty focusing up close

In these cases, the brain is healthy but the image it receives is blurry. Glasses sharpen the signal.

When the Eye Is the Problem. Some conditions damage the eye or retina itself, and glasses cannot fix them.

Cataracts: cloudy lens, reduced contrast

Macular degeneration: loss of central detail

Glaucoma: gradual peripheral vision loss

Retinal disease: disrupted photoreceptor function

When the Brain Is the Problem. Vision can fail even with healthy eyes.

Stroke or brain injury

Visual processing disorders

Difficulty recognizing objects or motion

Here, the eyes detect light, but the brain cannot interpret it correctly.

When to Get Checked. Seek evaluation for sudden vision changes, loss of peripheral vision, flashes of light, or vision changes with headaches or neurological symptoms.

I hope you enjoyed learning about the visual system!

With love,

Dr. Azura Plantiff

Selected References

Masland R. H. (2012). The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron, 76(2), 266–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.002

Hubel, D. H., & Wiesel, T. N. (1968). Receptive fields and functional architecture of monkey striate cortex. The Journal of physiology, 195(1), 215–243. https://doi.org/10.1113/jphysiol.1968.sp008455

By Eric R. Kandel, John D. Koester, Sarah H. Mack and Steven A. Siegelbaum (2021). Principles of Neural Science, Sixth Edition, 6th Edition. McGraw-Hill.

Livingstone, M., & Hubel, D. (1988). Segregation of form, color, movement, and depth: anatomy, physiology, and perception. Science (New York, N.Y.), 240(4853), 740–749. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3283936

Nassi, J. J., & Callaway, E. M. (2009). Parallel processing strategies of the primate visual system. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 10(5), 360–372. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2619

Friston K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory?. Nature reviews. Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2787

Share Dialog

Share Dialog

No comments yet